一般一门语言有多少单词呢?作为外语的学习者,我们需要学习多少个词?这个问题远比看起来的要更加复杂。下面的问题取自Paul Nation教授(惠灵顿维多利亚大学)撰写的书 "Vocabul-ary in Another Language":我们是否应该把book和books算作不同的词?像百事可乐的产品名称算单词吗?如果一个词的不同形式不算是不同单词,那像mouse和mice的形式也不应该分别解释吗?

根据Nation所写,现代英语的最大词典是"Webster's Third New International Dictionary" ,其中包括约114.000“词系”。什么叫“词系”?词系就是一组相关的单词,speak、speaks、speaking、spoken、speaker、speakers、speech。词系中单词的共同核心是本词系的“基础词”(英lemma):比如,上面单词的lemma是speak。“词根”的概念将在后面讨论,因为它构成了其自身的问题。Nation的估计是,受过教育的英语母语使用者能识别的词系数量在两万左右,如果算上其复合和衍生的单词,则大约有八万个。然而,我们知道,上述数据是针对受过教育的母语使用者而言的。

我们不应该害怕于这个数字。应当注意的是,语言分为不同的使用域,即在不同的范围内所使用的词汇。比如说,与朋友闲聊和撰写学术文章这两个情况一般选择相当不同的词汇。根据Paul Nation和Teresa Mihwa Chung发表的文章(2003),最主要的四个使用域有:

高频词:定义为英语最常见的两千个单词和词系(经常称为“普遍使用词汇表”,英"General Service Vocabulary")其中包括像the、a、at、for的基本词汇。这部分包括构成英语的最基础语法框架以及最简单、非专业的的句子。高频词覆盖了大约80%的学术文章和大约90%的非正式谈话。

学术及技术词:以Coxhead (2000)所确定的 “学术词汇表”为准,其中包含570词系,是在学术、正式、书面言语当中最常见的词汇,增加基本的各种专业特用词。涵盖学术文本的8.5% ,报纸的4%,不到小说的2%,专业文章的大约5%。

低频词:词典中的大部分单词属于本种类,这些单词不属于上述两个种类,简单地说,只是偶尔才被使用:这些词大多积累于英语发展的悠久历史中,虽然还没有完全过时,已经不属于常用词汇的范畴。 这些单词大概涵盖书面语言的5% 。

不过,值得强调的是,某个词的出现频率和其所包含的信息是成反比的,即不常用词经常是最重要,最有意义的。请检查下面引自一本医学课本的段落(高频词是正常字体,学术及技术词为黑体字,低频字是斜体字 ):

The thorax (chest) is the superior part of the trunk between the neck and the abdomen. It is formed by the 12 pairs of ribs, sternum (breast bone) costal cartilages, and 12 thoracic vertebrae . These bony and cartilaginous structures form the thoracic cage (rib cage), which surrounds the thoracic cavity and supports the pectoral (shoulder) girdle. Along with the skin and associated fascia and muscles, the thoracic cage forms the thoracic (chest) wall, which lodges and protects the contents of the thoracic cavity — the heart and lungs, for example — as well as some abdominal organs such as the liver and spleen. The thoracic cage provides attachments for muscles of the neck, thorax, upper limbs, abdomen, and back. The muscles of the thorax itself elevate and depress the thoracic cage during breathing. Because the most important structures in the thorax — the heart, trachea, lungs, great vessels, and the thoracic wall itself — are constantly moving, the thorax is one of the most dynamic regions of the body.

(汉译:胸部是颈部和腹部之间的躯干上部,由十二对肋骨、胸骨、肋软骨和十二个胸椎(图1.1)所构成。上述骨头和软骨形式胸廓,后者周围胸腔,同时支持肩带。加以皮肤和相关的筋膜和肌肉,胸廓形成胸墙,后者保护胸腔的内容 — 比如心脏和肺部-以及腹部的器官,比如肝脏和脾脏。胸廓给颈部、胸部、上肢、腹部和背部的肌肉提供支架。呼吸时,胸部肌肉提升和抑制胸廓。因为胸部最重要的结构,即心脏、气管、肺、大血管和胸墙本身不断地运动,胸部是身体最有活动的部分之一)

总结一下,最常用的词汇负载最基本的信息以及口语的大部分词:大约2,000词足够。不常用的词传递更多的信息,也是书面、正式、学术言语的必要组成部分。

学习2000词不是个大挑战,因为可以很容易背下来,但如果想记忆大量的词汇则需要一个更系统性的学法。如果把这些词汇当作彼此无关的隔绝元素而尝试去仅靠记忆力死记硬背,这不仅是对时间,也是对智力资源的巨大浪费。母语使用者对于其母语词汇的掌握,主要是通过反复接触和记忆达成,学习的时间涵盖童年和青年,大约从出生到18-20岁。并且,母语使用者在这个漫长的过程中能形成某种对生词的“感觉”,这种“感觉”经常允许他们把生词的意思猜出来。

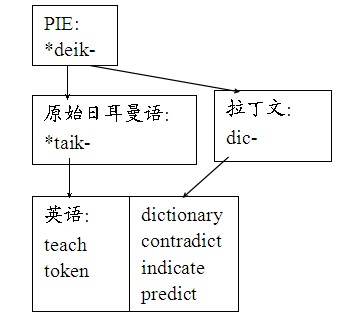

什么是这种“感觉”?拿一个“词系”举例子,比如以单词"teach"为核心的词系,由其可以衍生"teacher","teaching",以及动词"to teach"的不同形式:"teaches", "taught"。这些词之间的关系是毋庸赘述的。然而,其他更深层的关系对非专业学习者来说仍然非常模糊。动词"to teach"原意为“显示”,从而可以说明"token"(“标记”)也与之有关:两者溯于原始日耳曼词根*taik-“显示”。在此术语“词根”可被定义如下:本身也许不是一个独立单词、但可以形成各种具有共同核心含义的单词元素:往往这些衍生过程发生于历史中,其形式必然有所变化,所以词根经常难于辨认,甚至有些语言使用者自己从未意识到词根的存在。

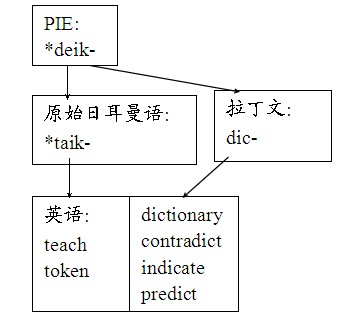

*taik-这个日耳曼词根当然是从PIE变过来的(请参考“什么叫PIE?”),重建的词根为*deik,“显示”。可能使许多读者惊讶的是,拉丁语词根"dic"也是从此来的,在拉丁语当中其含义是“通过话语显示、说”:像"dictionary"、"contradict"、"indicate"、"predict" 的许多英语单词也是从这个词根来的。拉丁词说法"vim dicare"“显示自己的力气”形成动词vindicare“报仇”;英语单词"revenge"、"vindicate"、"vendetta"也是从这里演变而来。请考察下面的图表:

当然,语言真正的演变要比我们刚才讨论的要复杂的多,我们只希望上面的例子能足以说明:一般来说,单词不是彼此独立的存在,通过分析,我们可以将其构建成一个系统。分析之后可以看到大多数英语单词是同源的:除了原始日耳曼词根以外,英语正式/书面使用域当中的词汇大多来自拉丁语和希腊语,这两门语言都有非常丰富的材料,考察起来十分便利:因而能看到,追溯某个单词的来源,并不像第一眼看到的那么深奥难懂。

然而,对单词的追踪溯源、建立联系,并不意味着可以绝对摆脱背诵:在学习任何新知识的过程中,对某些基础知识的纯粹记忆是必要的。但我们的建议是,可以将记忆过程优化,将机械记忆减少到最低的必要程度,同时将其建立在对语言历史演变的理解基础之上。

参考文献

Baugh, Albert C. A history of the English language (5th ed.). Routledge, 2002

Nation, Paul, et. al. , Reading in a Foreign Language,Volume 15, Number 2, October 2003.

Nation, Paul, Learning vocabulary in another language, Cambridge University Press, 2001

McArthur, T. (ed.) The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford University Press, 1992.

How many words does a certain language have? As learners of a foreign language, how many do we have to learn? The question is more complex than what it seems at first sight. The following questions are taken (paraphrased) from Professor Paul Nation’s (Victoria University, Wellington) book Learning Vocabulary in Another Language,: Should we count book and books as the same word? Do we count the names of products like Pepsi? Is an irregular form like mice to be counted as a different word from mouse? Forms like walk (verb) and walk (noun) are to be counted as two different words?

According to Nation, the biggest modern dictionary of English is Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, with around 114.000 word families. What is a "word family"? A group of related word forms, such as speak, speaks, speaking, spoken, speaker, speakers, speech. The common element to the members of a word family (in this case, "speak") is called the lemma or base word. The term "root" will be discussed later on, because it poses problems of its own. Nation’s estimation is that educated native speakers of English know around 20,000 word families, which become around 80,000 words, i.e. inflected or suffixed words. Nevertheless, it should be stressed here that we are speaking about the vocabulary of educated native speakers.

We shouldn’t be scared by this number. It should be born in mind that language is divided in different registers, i.e. ranges or varieties of vocabulary to be used according to different contexts. This means that when talking two a friend and when writing an academic paper, the kinds of language we use are very different. According to another paper by Nation in collaboration with Teresa Mihwa Chung (2003), the following four useful registers can be identified:

High frequency words: Defined here as the most common 2,000 words and word families in the English language (termed "General service vocabulary"), they start with items such as the, a, at, for. These cover the most elementary words that give the grammatical framework of the language and the most elementary expressions, not connected with any particular field. It covers around 80% of the words of academic texts and newspapers, and around 90% of conversation and fiction.

Academic words and technical words: Defined by the "Academic Word List" (Coxhead 2000) this list contains a list of around 570 word families (not exactly words, then) most commonly used in written academic or formal speech, plus words used in specialized contexts. It covers on average 8.5% of academic text, 4% of newspapers, less than 2% of fiction, and about 5% of the words in specialized texts.

Low frequency words: These make up the majority of words in the dictionary and belong to none of the previous categories, and are simply rarely used: many of them were accumulated during the long history of the English language and although not yet fully obsolete, have fallen outside the range of common usage. These words usually cover around 5% of written texts.

Nevertheless, something that should be stressed clearly is the fact that the amount of information contained in a word and its frequency are often inversely proportional, i.e. rare words are often the most important and meaningful. Let’s take a look ate the following paragraph, taken from a medicine textbook (The high frequency words are unmarked, academic and technical words are in bold, low frequency words are in italics)

The thorax (chest) is the superior part of the trunk between the neck and the abdomen. It is formed by the 12 pairs of ribs, sternum (breast bone) costal cartilages, and 12 thoracic vertebrae (Fig. 1.1). These bony and cartilaginous structures form the thoracic cage (rib cage), which surrounds the thoracic cavity and supports the pectoral (shoulder) girdle. Along with the skin and associated fascia and muscles, the thoracic cage forms the thoracic (chest) wall, which lodges and protects the contents of the thoracic cavity — the heart and lungs, for example — as well as some abdominal organs such as the liver and spleen. The thoracic cage provides attachments for muscles of the neck, thorax, upper limbs, abdomen, and back. The muscles of the thorax itself elevate and depress the thoracic cage during breathing. Because the most important structures in the thorax — the heart, trachea, lungs, great vessels, and the thoracic wallitself — are constantly moving, the thorax is one of the most dynamic regions of the body.

Let’s take a look at one of its sentences: "The muscles of the thorax itself elevate and depress the thoracic cage during breathing". Only with the high frequency words we would obtain the following result: "The ? of the ? itself ? and ? the ? during ?". This means a very impaired comprehension of the text. Adding the academic and technical words provides a much better understanding: "The muscles of the thorax itself ? and depress the thoracic cage during breathing." Only the low-frequency word "elevates" provides a full understanding of the text, but nonetheless, the academic and technical words provide most of the most important elements in order to understand the main idea of the sentence.

To sum up to this point, the most frequent words cover the most elementary messages and make up most of the words in speech: for this, around 2,000 words are enough. Less frequent words convey more information, and are necessary for more complex subjects and for formal, academic language, mostly written.

Having to learn some 2,000 words does not pose a serious challenge, as they can be memorized easily, but having to learn a considerably greater vocabulary needs a more systematic approach. Trying to master such a bulk of data in an unorganized way, i.e. by pure memorization, without trying to understand the relationship between them, is a big waste of time. Native speakers, who learn largely by exposure and memorization, have at their disposal a big span of time, consisting in the years of their basic education, i.e. roughly from birth to 18-20 years, and on the other hand, when having to learn infrequent words, they have already built a "feel" for their own language that allows them to infer unconsciously relationships with other words.

Let’s take an example of what relationships can be built between word families. We spoke before of word families. One of those has the word "teach" as its nucleus. From there we can derivate "teacher", "teaching", and the different forms of the verb "to teach": teaches, taught. These relationships are obvious to everyone. Nevertheless, other relationships are kept hidden to the unspecialized learner. The verb "to teach" originally meant "to show", and thus the relationship with the word "token" can be hinted at: both come from an ancient Germanic root, *taik-, meaning "to show". Here we can define a root as a segment that by itself is not an independent word, but it can form words with a common nucleus of meaning: as often these processes of derivation happen through history, and so the outer appearance of the root can change, roots are often hidden to the users of the language.

Our Germanic root comes from a PIE root (See more about PIE in -link- What is PIE?), *deik- that means also "to show". What might surprise many readers is that this old PIE root is also behind the Latin root dic-, which in Latin means "to say" or "to show with words". This Latin root is behind English words like "dictionary", "contradict", "indicate", "predict" and many others. In Latin the phrase "vim dicare" "to show one’s strength" is behind the verb vindicare "to revenge", which in English produced (through many different pathways) words like "revenge", "vindicate" and "vendetta". The root vi- "strength" appears in words like "vigorous" and "violate". We can therefore trace a diagram like the following:

Of course much more complex relationships can be traced, but hopefully this example will suffice to show how words are not isolated entities, but through the aid of analysis, they can be grouped into larger families, into a system. Most words in the English language can be, after analysis, be shown to have cognates: if we take into account the fact that, as far as the vocabulary of written formal and academic material is concerned, besides indigenous Germanic roots most material comes from well-documented Latin and Greek, then it becomes clear that the quest for a word’s origin is often not as difficult and remote as one might think at first sight.

Of course, the use of this method doesn’t really mean getting rid of all efforts of memorization: a part of memorization is necessary when learning almost anything, but in this case what we are proposing is to optimize this effort, driving it to the necessary minimum and at the same time counterbalancing it with a systematic and active understanding of the history of the language.

Sources

Baugh, Albert C. A history of the English language (5th ed.). Routledge, 2002

Nation, Paul, et. al. , Reading in a Foreign Language, Volume 15, Number 2, October 2003.

Nation, Paul, Learning vocabulary in another language, Cambridge University Press, 2001

McArthur, T. (ed.) The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford University Press, 1992.

版权所有 2011-2015 北京云英一语教育咨询有限公司 Y-English All Rights Reserved

地址:北京市海淀区五道口华清嘉园商务会馆802

电话:400-876-3898 010-82863898 82863899 传真:010-82863897